Copyright 2004 by Dennis Dezendorf

|

Just before Christmas, the Lady and I were driving down the road and she was telling me about this guy at work who was talking about a falling block rifle. She couldn't picture it in her mind, and I couldn't describe it accurately. I saw a pawnshop and pulled in, telling her "Come on, we'll see if we can find one and I'll show you." The Lady loves pawnshops. She is especially attracted to those sparkly carbon crystals kept under glass at a pawnshop. We've found a couple of pretty good deals and she is a willing participant if I give her time to look at the jewelry. We walked in the door and I asked the counterman, "Got any falling blocks on the rack?"

I examined the rifle. The wood was pristine. The action was stiff. I dropped the block and peered down the bore. It looked brand new. The only fouling I could see looked like dust, down near the chamber end. The same type dust I have seen on rifles left sitting in the rack too long. I looked at the tag hanging from the lever, which said that it was a used rifle, and the price was $625 US dollars. I asked the counterman, "Has this rifle ever been fired?" "Doesn't look like it, does it?" he replied. "If it has been fired, it was only once or twice." I cocked it and tried the trigger. Stiff as a board, it broke at about 20 pounds. I noticed a set trigger, cocked the hammer, set the trigger and tried it again. It broke at about one pound. Hmmm. I handed the counterman the rifle and the lady and I walked out the door. Later that evening, I found myself searching for "1874 Sharps" on the internet. The Pedretti is one of the Italian replicas of that rifle commonly associated with the buffalo trade of the late 1800's in the United States. Original rifles can still be purchased although at figures that reflect the scarcity and workmanship of that era. Reproductions are available from a number of makers, both domestically and abroad. A person can spend just about any amount of money on a Sharps replica, depending on how he wants it set up. They can be had in any number of calibers, to include the "Big 50" calibers used by the likes of Kit Carson and Billy Dixon. Of the reproductions available, the Pedretti is down in the lower price range, and new rifles can be had for $800 - $900 US dollars. My research indicated that the Italian manufacturers made historically accurate rifles, down to the spacing on the tang for aftermarket sights. They also used the same lock geometry as the originals, resulting in little levers trying to move large springs. Trigger pulls were heavy and set triggers were usually fitted to counter the force necessary to move the trigger. The next day was Sunday and we had a day of shopping planned, getting ready for Christmas. When we drove by the pawnshop, it was closed. Sunday night, while the Lady played on the computer, I watched the movie "Quigley Down Under" on the DVD. I wanted that rifle. I knew my money would be tight leading up to Christmas. I mentioned my desires to the Lady. "Go put it on layaway." Monday afternoon I did just that. I walked into the pawnshop after work and put the Sharps on layaway. The .45-70 cartridge was adopted by the US government in the late 1800's. It was chambered in a variety of rifles and is enjoying a resurgence of popularity lately as sportsmen rediscover how lethal a large heavily constructed bullet can be. Cowboy Action shooting is in part responsible for the reawakened interest in the cartridge. It was originally loaded in two basic loadings. The 45-70-500 was a .45 caliber, 500 grain bullet over 70 grains of black powder. The 45-70-55 was the same 45 caliber, 500 grain bullet loaded over 55 grains of black powder. Some say that the 55 grain loading was designed for carbines. I've never experienced this caliber in my personal battery, and didn't have any supplies for loading it. I've been shooting muzzleloaders for over 20 years and know the basics of loading black powder, but had never tried that propellant in a cartridge. I determined that this rifle would never be fouled with smokeless powder. I would shoot black powder cartridges in it exclusively. I needed brass, primers, molds, reloading dies, and time to gather all the accoutrements before the rifle came home.

Lets talk about muzzleloaders for a moment. When you seat a muzzleloader ball down on the powder, you seat the ball or conical bullet directly on the powder. Airspace under a black powder bullet is bad. We are careful to mark the ramrod to make sure we get the same compression each time. When we seat the ball to the mark we have made on the ramrod, we know that we have the same compression on the powder and that the ball is firmly seated on the propellant. Black powder cartridge reloaders want the same thing. The bullet has to be seated on the powder with no airspace in the cartridge. Black powder cartridge reloaders have also learned that they get best accuracy when they put a wad or grease cookie between the powder and the bullet. Because black powder is granular, when it settles into a column (like dropping it into a straight walled case), there is air between the granules of powder. Some reloaders have devised drop tubes, compression dies, and all manner of devices to settle the powder, minimizing the airspace in the case. I'm a simple kind of guy, preferring to run my life on the KISS process. I also wanted to minimize the impact on my checkbook. I also did not want to reinvent the wheel. The old timers were getting fine accuracy and utility from these rifles long before I was born. So I called my buddy, Junior Doughty. Junior has played with .45-70 and is familiar with the peccadilloes of loading for it. He promptly sent me some cast bullets in two weights and some Buffalo Felt Wads, along with instructions on how to use them. I went to my local grocery store and bought some hog lard, 79 US cents. I also dug around in my reloading stores and found a block of genuine, raw beeswax.

Late in January, I finished paying off the rifle and brought it home. The counterman told me that the rifle had set unappreciated and unloved on his rack for several months before I put it on layaway. Until then, I was the only guy who expressed an interest in it. When I put it on layaway they removed it from the rack and stored it in the safe with the other guns. Since then, three guys came in wanting to buy it. He told them "Tough." The first night it was home, I took it apart to look at the lock and see if I could figure out why the trigger pull was so horrible. I have a Thompson Center Renegade with set triggers and the front trigger on that rifle trips at about six pounds. The set trigger lets it go at about half a pound. I pulled the lock off the Sharps and was pleased to find that it is a lot like the Renegade lock. Before I go any further, I have to say this: Adjusting triggers, resetting sears, stoning lockwork is potentially dangerous. Without some formal training and a good dose of common sense, the delicate interaction of the lockwork might be damaged by tinkering with it. I did what I did on my rifle. It might not work on yours, and I don't recommend that anyone do what I did. Sear engagement is critical to the safety of a rifle. If you take apart your rifle and tinker with the lock, you might create a dangerous condition that could result in inadvertent misfires, and potential injury or loss of life. Don't do anything to your lock unless you are willing to assume the risk. That said, when I pulled the lock off the Sharps, I saw that someone had been in there before me. The sear had some burrs on it that engaged the tumbler with a vengeance. I took the stone out and worked the burrs off the sear. While I was in there, I generally smoothed everything, getting off burrs, file marks, and tool marks. I reassembled the rifle. The set trigger wouldn't work. Damn. I took the rifle down again and inspected the trigger assembly. The set trigger has a spring that bears against it. When it is set, it places tension on the trigger bar that trips the sear. That spring wasn't bearing on anything. I adjusted it, lubed the lock while I had it out. Reassembled everything. It worked. The main trigger broke at about eight pounds. The set trigger tripped at something under a pound. While tinkering with the triggers I got online and looked at some sites that discuss set triggers. I wound up at Track of the Wolf where I learned that the Pedretti triggers are just exactly like the triggers on the original 1874 Sharps rifles. They don't have a backlash screw and must be set before cocking the lock. This is important to know. Newer triggers and those found on replicas today allow the shooter to cock the lock or set the trigger in any order. Triggers without a backlash must be set before the lock is cocked. That doesn't make the rifle unsafe. You must set the trigger before you cock the lock to the half-cock notch. In newer rifles like my Renegade, the trigger can be set just before I am ready to shoot it. On the Sharps, the trigger must be set first. It isn't safe or unsafe, it is just different. The best safety for any shooter is the brain between your ears. While I had the screwdrivers out, I installed the Creedmore sight. It went on just like it was supposed to. Five minute job. No problems. My sight does not have a windage adjustment. I will order a globe sight for the muzzle end later. I can drift the front sight in the dovetail to adjust for windage, and it has been my experience that once set for windage, any rifle will shoot where it looks. The rifle came with a silver blade sight on the muzzle. It looks elegant sitting out there. The only problem with it is that I cannot see it, except in bright sunlight. When the checkbook recovers, I will order a globe sight, probably with a bubble level. The next night, I decided to load some ammo for the rifle. The only black powder substitute I had available was a pound of Cleanshot. I bought it last year when I ran out of Goex powder for my Renegade. Goex powder is made in Louisiana, but for some reason there is only one retailer in the state that stocks it. I like Goex powder because it is real black powder. I've used Pyrodex too, but decided to try Cleanshot the last time I bought powder. It cleans up easily, seems to give good service in my muzzleloaders. I'll probably go back to Pyrodex later, but the first loads will be Cleanshot.

Lets take a minute here and talk about indexing. One of the things the cast bullet shooters have learned is that indexing a bullet with the case, and indexing the loaded round in the chamber tends to give better accuracy. I'm sure the Cast Bullet Association could explain it in more detail, but take my word for it; orienting the bullet in the case the same way each time, and orienting the loaded round in the chamber the same way each time, leads to better accuracy.

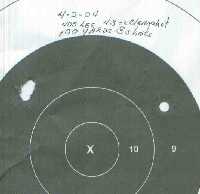

For folks that say a shooter has to spend over a thousand bucks to get fine shooting with a Sharps rifle, I say nonsense. This Pedretti is one of the least expensive of the bunch. My expenses getting the rifle to shoot are detailed in this article. So far, I have $722.10 spent on the rifle and accessories I didn't already have. I am still going to put a globe sight on the front of it. Track of the Wolf will sell me one for about $25.00, so for under $750.00 including dies, brass, etc., I will have a Sharps I can shoot for fun, for competition, for meat. Let those rich fellows spend their hard earned money. I'll spend what is left over buying baubles for my lady.

|