Copyright 2004 by Dennis Dezendorf

|

Sometime last month, July, 2004, I went into a pawn shop to look at lever action rifles. At the used gun rack, I found an assortment of Winchester and Marlin lever guns, the vast majority of them in .30-30. I'd never hunted with that old, efficient caliber. My scoped Marlin .35 lever action looks like new and has given me good service for many years. But I'd been thinking about getting a beater lever action with peep sights, a rifle I could throw behind the truck seat and not worry about scratches or a fragile scope. The woods along the rivers and bayous in Louisiana where I hunt are mixed-hardwoods bottom land. If you climb a hill you find a few pines. Logging roads and oil field service roads wind through those woods. On a good day you can see a hundred yards. On a foggy day you might see 25 yards. My personal longest shot at a deer has been 75 yards, at a spike buck. Peep sights are fine for my kind of hunting. I like shooting scoped bolt action rifles with hot bottlenecked cartridges at long ranges. Nothing in the world is wrong with that, but this truck/beater rifle was going to be something different. A short, handy, iron-sighted carbine, in a proven caliber and with a winning track-record. It had to be absolutely reliable, with nearly universal availability of ammunition. The Winchester 94 or Marlin 336 rifle in .30-30 sure meets that criteria.

I said to the salesman, "Tell me about this Winchester." He walked over and held the rifle. "Well, it isn't a pre-64, but it doesn't have a safety or a rebounding hammer, so it isn't new, either. The receiver has some scroll-work engraved on it, and it looks like a commemorative, but I'm not sure what it is, exactly." We got his bore light and I saw that the bore was okay, with no wear out at the end, near the muzzle. Sometimes, people who don't know about cleaning rods will destroy a rifle by not using a bore guide. The rod, working from muzzle end of the barrel will scrub off the rifling, destroying the bore. The crown of the muzzle looked good too. The rifle seemed to cycle easily. "How much?" I asked. "Aaah, I dunno. I was getting ready to package that with another bunch of rifles for a wholesale sale. Give me $125.00 and it's yours." I wrote a check and took it home. That afternoon I did a little research. The rifle had been made in 1965. I went to the forum at Leverguns.com and asked the guys if they could identify the rifle. Turns out, it is known as an Antique Carbine, the first non-commemorative commemorative. One fellow described it as "Winchesters first attempt at increasing the horrible sales of the post-64s by putting a dress on a pig." The next weekend saw me up at Junior's house. Junior Doughty, my hunting buddy, drinking buddy and yarning-around-a-campfire buddy knows a lot more about Winchesters than I do. He promised to help me take it apart and check the headspace to make sure it was safe to shoot. We were both surprised when we took the gun apart and found almost no wear. The bluing on the link and the lever were almost 90% intact. While the outside of the gun had been abused, the interior looked pristine. Junior and I shot it a few times with his reloads and then cracked open a few cool beers and told some lies.

Headspace gages come in three flavors, Go, No-Go, and Field. The Go and No-Go gages are used by gunsmiths when setting a new barrel. Old soldiers remember the Go and No-Go gages issued with every M2 Browning machine gun for doing barrel swaps. Field gages tell if a particular rifle is safe to use with factory ammunition. We used Junior's Field gage on my rifle and found that the headspace was fine, actually on the tight side.

910-999-058 and costs $20.16. It fits in the hole you can see in the first picture, and you can see it installed in this picture. If I were truly on a budget or didn't want the saddle ring on my rifle, I would have purchased the saddle ring plug, 910-941-068, which costs $2.59. I wanted the saddle ring. It was easy to install, requiring no tools at all. I simply screwed it into the hole with my fingers, stuck my index finger through the ring and tightened it. The receiver sight is a Williams Foolproof. You can find it at Midway USA, www.midwayusa.com. It is part number 712881 and costs $58.95. This number will get you the Williams Foolproof for the Winchester 94/Marlin 336. It also comes with a Williams Firesight. Some folks like the Firesight. I don't. I prefer the standard bead that came on the rifle, so I kept it. The Williams Foolproof mounted easily with a common screwdriver. It took about ten minutes to install the sight and saddle ring. The instructions that came with the sight were wonderfully accurate and easy to follow. A word of caution: Williams sights come in a dizzying array. There are literally hundreds of them in different configurations, for different rifles. If you own a Winchester Angle Eject, you will need to order a different sight. The sight for the current crop of Winchester Lever Action rifles is Midway #825978 and comes with the Williams Firesight front sight, for $58.95. If you don't want the Firesight, both rifle sights can be ordered without it, and it still costs $58.95. Some truly frugal outdoorsmen might opt for the Williams 5D sight, which is not click adjustable and sells for $32.95. Be sure you order the correct sight for your rifle. Once the receiver sight is installed, the factory rear sight needs to be removed. That is as simple as tapping it out with a punch and hammer. Removing the factory sight leaves a dovetail in the barrel. I forgot to order a dovetail slot blank, but Brownells stocks them (962-000-034 for $4.95). I'll get one the next time I make an order.

I went to Wal-Mart Finally, the time came to shoot it. I was eager to see what a beater rifle with iron sights and dirt cheap ammo would do. I drove out to the range sponsored by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries at Woodworth, Louisiana, and set up some targets. I spent about an hour, and most of the ammo, getting the new sights to shoot the bullets onto the paper. Then I set up some targets at 50 yards and settled down on the bench to see what a $125 pawn shop rifle and cheap mass produced ammo would do. To say that I was amazed was an understatement. I am still astounded.

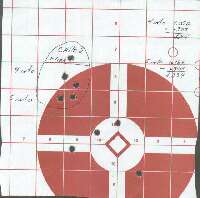

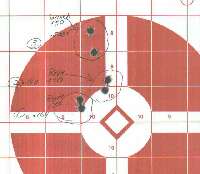

A minute of angle is commonly defined as one inch at 100 yards. That has long been a benchmark. A half inch at 50 yards, one inch at a hundred yards, two inches at two hundred yards, you get the picture. Minute of angle (MOA) is a measurement of shot dispersion. Many hundreds of dollars are spent in the shooting games trying to shrink a group down past that magic inch. The benchrest boys have led the way, and they have rifles capable of quarter-minute accuracy. The manufacturers have made great strides in bedding and manufacturing technique over the past thirty years, and we generally understand now that a good bolt action rifle, with carefully constructed hand loaded ammo should be capable of MOA accuracy. We tend to think that bolt rifles are generally capable of better accuracy than leverguns. Most are, I'm sure. For a long time, the generally accepted accuracy standard for a lever action rifle was three or four minutes of angle. That is to say that if a levergun could put its shots into three or four inches at a hundred yards, we should be happy, and know that we can kill deer with that rifle. And that is still a true statement. If a hunter can routinely hit something four inches wide at 100 yards, he will do well in the hunting fields. The Remington online ballistic tables tells me that the Remington Express, 170 grain, Core-Loc bullet in caliber .30-30 should be (for a 100 yard zero), 3/10 inch above the line of sight at 50 yards, and 2.7 inches below the line of sight at 150 yards, with enough energy to take down a deer if I put the bullet in the vital heart-lung area. I wanted the bullet to be about a half inch above the bull's-eye at 50 yards, and I wanted the best possible accuracy out of a beater rifle and cheap, discount store ammo. I had six rounds left. Four rounds of Remington, and two of Winchester. I had already decided that the rifle liked the Remington ammo, so the sights would be set for that. The rangemaster called for a cold line and we all opened our actions and went out to post targets. I took down the target you just looked at, and put up another one. I decided that when he called the line HOT, I would hunker down and see how much accuracy I could wring out of the rifle. This isn't about hunting accuracy, although an accurate rifle helps. I wanted to see if I could get serious with my shooting and make the smallest groups possible, to see exactly how much I could count on the rifle. If I screwed the shot in the field, then it was my fault. I borrowed a pair of binoculars from the rangemaster so I could see the bullet holes in the target. He called the familiar commands of "Ready on the Right, Ready on the Left. The firing line is now hot." I loaded two rounds of Remington ammo into the rifle, wiped the sweat out of my eyes, and peered through the Williams peep. Two shots, clean trigger break. I looked through the binos and saw one hole in the target. Huh? I adjusted the sights for a bit more right windage and loaded the last two Remington rounds. Two shots, two clean trigger breaks. I looked through the binoculars and saw one hole in the target. What the sh**? I loaded the last two rounds of Winchester ammo and fired them as carefully as I knew how. Two shots, two clean breaks. I picked up the binos again and looked downrange. Two holes in the target. I relaxed at the firing line, sorted my brass, and made sure the action was open. I talked with a fellow on the next bench who was also finished shooting. Before long, the command came to open actions and step away from the weapons. The line was cold. Go forward to post targets. I walked downrange.

Group two, fired a minute later with Remington ammo after the sights had been adjusted for the final time, has an outside measurement of .496 inch, which gives us a center-to-center measurement of .188 inches. That is half MOA work, too. Group three, fired with Winchester ammo, has an outside measurement of .816 inch. Correcting for center-to-center, we get a measurement of .508 inches. That is just outside of minute of angle dispersion. For reference, the target is one manufactured by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. The squares on it are an inch each. You can print my targets off the computer, use the inch squares as a reference and verify my math if you like. I have the paper targets. What does this target tell us?

Finally, we learn that a Frugal Outdoorsman doesn't need to mortgage the home to buy an accurate rifle/ammo combo. I have less than $200.00 tied up in this rifle, sight, and ammo. If I do my part, it will do its part.

While buying ammo at Wal-Mart

|